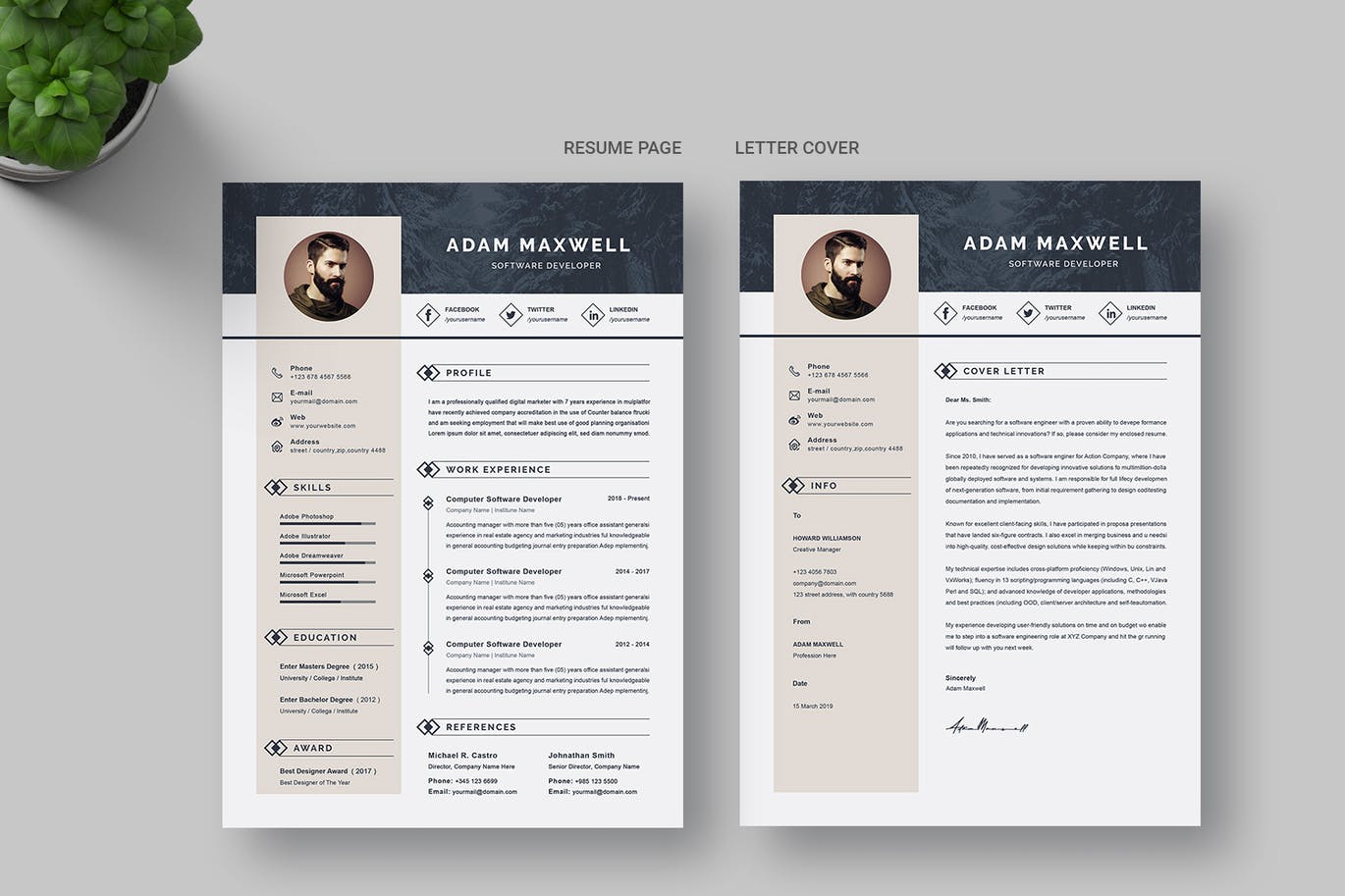

📥8+ Excellent Resume Templates Download

Cinematography is more than just capturing beautiful images. For Roger Deakins, one of the most respected cinematographers alive today, it’s about creating a seamless visual experience that serves the story. In this post, we’ll explore Deakins’ thoughts on cinematography, looking at the craft beyond the technical aspects and dissecting what truly matters when telling stories through visuals.

Cinematography Is About Storytelling, Not Pretty Pictures

Deakins believes cinematography isn’t about crafting individual shots that stand out but building a cohesive film that keeps the audience engaged. A visually stunning scene can actually be a distraction if it pulls the audience out of the story.

The goal, he argues, is to make every element work as part of a whole. Extraordinary photography isn’t the priority—it’s creating a visual language that sustains the story. If people remember the film but not specific “cool shots,” then the cinematographer has done their job.

This philosophy rejects the idea of making things “pretty for the sake of pretty.” Cinematography should flow naturally into the narrative, letting viewers focus on the emotional core instead of the visuals.

Technology Isn’t the Focus

Deakins downplays the importance of specific cameras and technical conveniences. For him, whether you’re using an Alexa, RED, or even an iPhone, what matters is how you use the tools you have. He suggests that too much focus on equipment can become a distraction, keeping filmmakers from truly telling their stories.

Instead of obsessing over pixels and gear, Deakins is fascinated by how simple choices—like camera placement or how light falls—affect how a scene feels. A shift in perspective or repositioning a lamp can drastically change how a moment resonates with an audience. It’s not the tool but how it’s wielded that counts.

When to Move the Camera

A question every cinematographer faces: to move the camera or not? According to Deakins, movement should always have a purpose. There are times when tracking a character strengthens the story, but there are moments when a static camera is more powerful. Understanding when to hold back and let the audience observe is critical.

He draws inspiration from directors like Jean-Pierre Melville and Michelangelo Antonioni, whose camera movements always had intention. Deakins compares it to watching a powerful performer; if the scene already holds enough gravitas, unnecessary movement risks taking attention away from the subject. Simplicity, as he puts it, often delivers the strongest emotional impact.

A Style That Matches the Project

Deakins says he doesn’t have a “style” but adapts his approach to suit the film he’s working on. While he leans towards naturalism, he emphasises that “naturalistic” doesn’t always mean “realistic.”

For instance, a night scene might not reflect exactly how the human eye sees it. Instead, it’s about creating a version of reality that fits the mood and narrative. His lighting choices aim to immerse audiences in a believable world without pulling them out of the story. Realism, he believes, is as much about perception as about accuracy.

Planning vs. Spontaneity

Preparation is essential, but so is staying open to surprises. Deakins meticulously plans his shots, especially when the timing of natural light plays a big role, as it did in “No Country for Old Men.” He charts the angles, time of day, and even sequences where second units take over.

However, he also allows room for “happy accidents.” Sometimes, unexpected moments—like light streaming through a window—can present opportunities to enhance a scene. Rigidity can stifle creativity. He describes his work as a balancing act between planning and adapting in the moment.

Lighting for Emotion, Not Just Coverage

Deakins isn’t interested in lighting for the sake of filling space. Every light source has to contribute to the feel of the scene. He critiques the traditional mindset of lighting setups—front key, backfill, kicker—as missing the point. What matters is what the light makes the audience feel.

Every decision, from how shadows fall to the presence of practical lights, needs to serve the atmosphere. If a lighting choice feels unjustified, it risks pulling viewers out of the film. For Deakins, believable lighting doesn’t have to be literal; it just has to feel real.

The Power of Lens Choices

Deakins is firm about the impact a lens can have on the audience’s connection to a subject. A close-up captured with a wide lens creates a very different emotional effect compared to a long-lens perspective. He prefers lenses that put the audience in the character’s space, echoing the natural closeness and interaction we experience in real life.

He avoids excessive multi-camera setups, except when absolutely necessary. Every shot should be intentional, framed with the audience’s emotional experience in mind.

The Danger of Overcomplicating

Deakins warns against the temptation to prioritise complexity over storytelling. Flashy camera moves, heavily filtered lighting, and dramatic depth of field effects might look impressive, but are they meaningful? For him, every visual choice must ask, “Does this serve the story?”

Simplicity doesn’t mean settling for less—it means eliminating distractions. The best cinematography doesn’t announce itself. Instead, it gently draws viewers into the world, allowing them to focus on the characters and narrative.

Roger Deakins’ cinematography philosophy boils down to one thing: serving the story. Whether it’s camera movement, lighting, or lens selection, every decision should aim to enhance the viewer’s emotional connection. By keeping things simple, purposeful, and grounded, Deakins proves that the most impactful cinematography often goes unnoticed. As he says, the ultimate compliment isn’t “What a beautiful shot,” but “What a great film.”

Leave a Reply